At the Twin Cities Agenda, one of our main areas of focus is on local food and drink. At its best, it is writing that also discusses the importance of food and drink: The things we eat at home with our families. Local ingredients that become stories told through plates, glasses, silverware. The relationship restaurants have with the neighborhoods that surrounds them, the impact they have on the landscape, the mission and passion and vision of their founders and chefs – the history and recipes that started it all – and the staff, the servers and bartenders, the dishwashers and bussers, the butchers, farmers, and fishmongers who help bring these dreams to life.

We don’t always achieve this goal. But we try. And we try, really, because of one man. Anthony Bourdain. The chef, writer, and enthusiast who never favored deadlines, social media clicks, or whatever might sell best over the quality and integrity of his work in a digital age.

He was not the first such writer, of course. But M.F.K. Fisher’s poetry and whimsy is something of the past, from a time, unfortunately, that we will never know. Anthony Bourdain brought it into the future, or at least created the roadmap of where to go for the dining and diners of today. He reminded us that food is for everyone; food is at once for one and for all, and all food, from highbrow to low, is awesome. It will always tell a story, and represents culture in a way few other things can. And, simply, that it is meant to be eaten and enjoyed –

As legendary author Jim Harrison (1937 – 2016), who Bourdain admired and spent time with in Livingston, Montana, stated plainly, “How feebly the arts compete with the idea of what we’re going to eat next.”

Anthony Bourdain didn’t spend much time in Minnesota. He visited St. Paul’s Saigon (now iPho by Saigon) in 2002 while on A Cook’s Tour. Minneapolis made it into only one episode of his TV work, and that was in the “Heartland” episode of No Reservations in which he visited the now-shuttered Doug Flicker restaurant Piccolo. He said it was one of the best dining experiences he had experienced in the United States. We cheered. It gave us hope that the Twin Cities might actually be the dining destination we knew it to be.

I had long hoped to convince Mr. Bourdain to come and spend a few more days in St. Paul, stroll through the cobblestone streets and 19th century architecture, share with him the joys of the city, eat good food, drink local beer and spirits, end up somewhere along the banks of the Mississippi beneath the Robert Street Bridge and the blinking red “1” of the First National Bank Building. We might have walked through the stalls of Hmongtown Marketplace and discussed the impact and importance of Hmong immigrants from Laos, Vietnam, China, and Thailand who made their home in Minnesota after the “Secret War” in Vietnam – and how a frigid city like St. Paul has benefited endlessly from their presence. We would have eaten injera and misir wot at Fasika, visited District del Sol for tacos and tamales, ordered shellfish at Meritage, booked a table at Mucci’s after drinking Hamm’s at The Spot (since 1885). And then I would have told him that, while Mucci’s might be our new gold standard, DeGidio’s still has the best red sauce in town (unchanged since 1933), and Cossetta, and Carmelo’s, and Yarusso Bros keep utilitarian Italian thriving in the city as well.

St. Paul is not a flashy sort of city. St. Paul is a blue-collar town, rich in history set along North America’s longest river. There are old restaurants still run by the family members of original owners that tell us tales about how the city has changed, and how that exemplifies the changes found across the United States as a whole. There are new, exciting places that look to the future. There is culture and diversity in food. Not flashy, but special to the people who live here.

That is perhaps what I (and the thousands of other fans of Bourdain’s show and work) appreciated most about him: It did not need to be flashy to be worthy. It did not need to be perfect. It certainly did not need to be backed by millions of investment dollars and celebrity endorsements. It was never wealth porn he was making or something that was for some but not for others. Everything and everyone, he told us, is interesting when we sit down to eat; the great equalizer: We eat together. Food is the thing that always has and always will meet us halfway.

It would make for good television – I thought. He would love it here as much as we do. I still believe this to be true. Though my goal shifted, at some point, from trying to convince him (or anyone) to come and force a story to simply supporting the places that would make him, or anyone, want to visit on their own. It’s a more inward-looking approach, I know, in an age of self-promotion and narcissistic grandeur. But we vote quietly with our wallets.

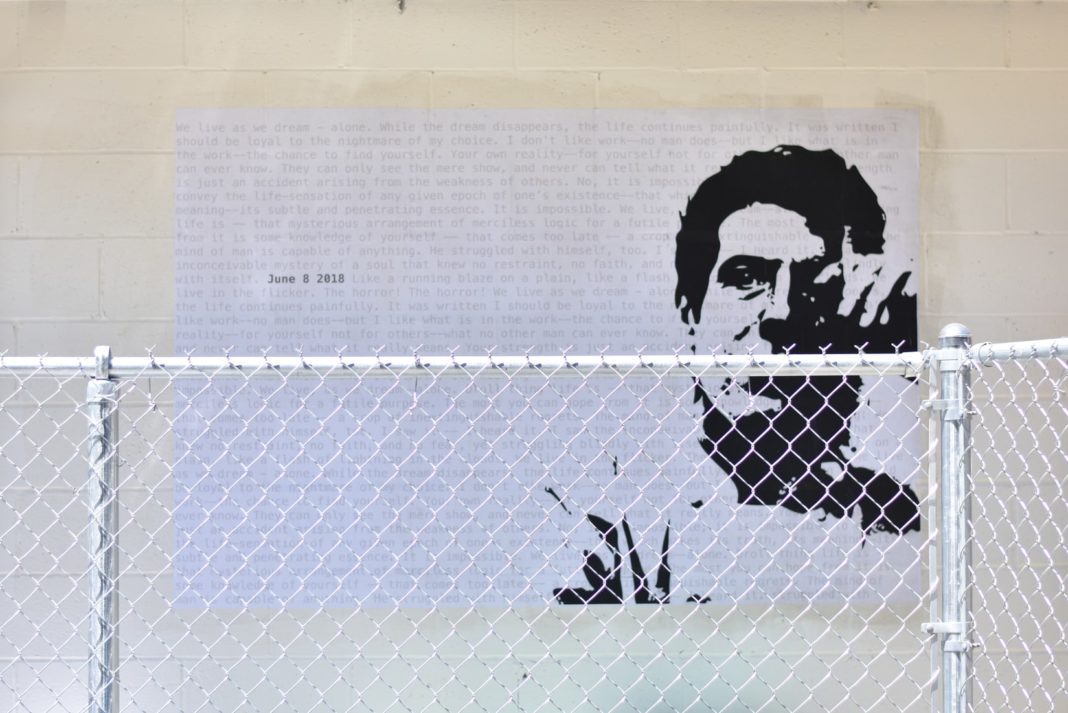

Bourdain, who truly defined the notion of lust for life, is no longer with us. Whether he is sitting down now to some grand feast in the sky or lives on only in reruns and Netflix-saved episodes of his various shows, is not for me to say. He will never make another episode. He will never tell another story of unseen people and places, discovering for himself and then sharing the magic of the world. He will never come to St. Paul.

But I still try and look at the city, and any city that I visit, in the way that he might have. Delicious is more state of mind than activity. It is not a standard set by anyone else. And the reasons why we eat are just as important.

This is what I learned, first from his Kitchen Confidential and then throughout his nearly two decades of writing and making television. While I was a teenager, and the kitchens of summer jobs were the same sweaty dens of sin and flavor he described, and on the flip side while sitting down to dinner with candles and white tablecloths. As I grew to appreciate food, especially food shared with friends and family, in new and exciting ways. As I learned how to please a nagging, gnawing hunger. How to satiate an appetite for the unknown. How to enjoy life and everything in it. This remains true forever – or at least until we are all finally, completely, happily, full.